Pack two, at long last; I promise it isn't my intention for this to become a quarterly publication...at any rate, on to the cards:

As a Braves fan, this one was a no-brainer, although I love the Ballard mid-windup with the leg kick, Matt Williams with all the weight on his toes, ready to pounce, and Calderon with the top button open, chains glinting in the sunlight, wearing what I can only think to describe as full-on driving gloves.

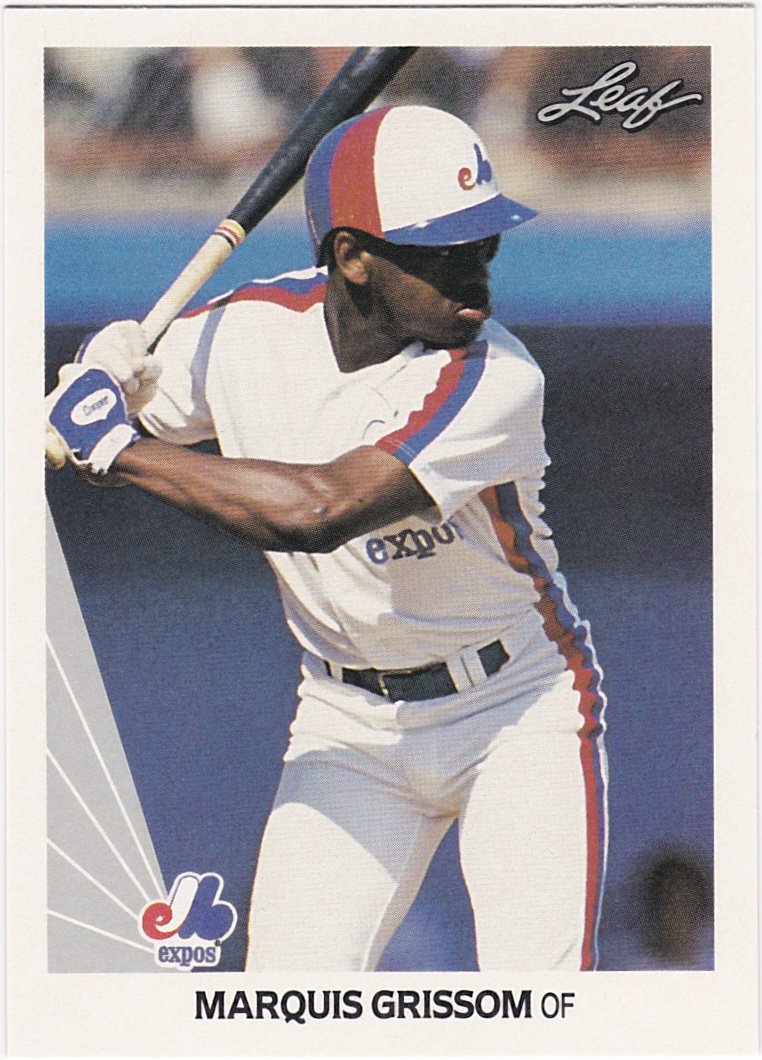

For me though, this pack is all about Marquis, the rookie in Montreal, still five years away from securing the final out in the first Atlanta World Series victory I was alive for.

The card itself: Grissom is locked. Look at how gripped this guy is and how unwavering his focus. I'm worried he's going to turn that bat into sawdust before he gets the chance to swing it.

For the stat-heads: Four-time gold glove winner, 2,251 career hits, 227 HR, NL leader in steals in '91 (76) and '92 (78), first in outs made in '92 and '96. .272/.333/.442 career slash line. One of the crazier elite SABR clubs Marquis belongs to is the 2,000 hits, 200 homers, 400 steals cohort. He is one of only ten major leaguers who have achieved it. Craig Biggio, Roberto Alomar, Barry Bonds, Rickey Henderson, Paul Molitor, Joe Morgan, Johnny Damon, Bobby Abreu, and Jimmy Rollins are the other nine.

I'll always remember Marquis as the only Atlanta native on the 1995 World Series team, and it will always bum me out that he was dished along with Justice for Embree and Lofton. There's just something awesome about a hometown hero on your roster, something surely not lost on Grissom, who played a role in Atlanta native Michael Harris II's development in high school summer ball.

Still, I will always wonder what Marquis Grissom's career would have looked like if the strike in '94 didn't happen. There's a good chance he would never have been on the Braves.

Going into that season, the Expos were stacked. They were a league-leading 74-40 going into the strike, six games ahead of Atlanta, and could have been looking at a World Series face-off with the 70-43 Yankees. Instead, the franchise wouldn't make the playoffs again until they made the move to Washington; who knows how much longer a World Series run would have secured their place in Montreal for?

At the end of the day, Grissom was shipped to Atlanta after the strike took its toll on team finances, in what would become a series of career moves over his last decade in the league that would see him don Cleveland, Milwaukee, LA, and San Francisco uniforms, giving the team of the '90s a glorious two seasons.

One of the coolest things about the end of Grissom's career was that standout year in 2003, his first with the Giants, when he hit .300 with 20 homers and 11 stolen bases.

And one of the many cool things about him off the field? He bought his parents a house and did the same for his 14 siblings.

A hometown hero, indeed.